Why Cold Rooms That Are “Often Not Used” Are Most Prone to Problems

Many people assume that if a cold room is not used, it will be “hassle-free,” but in practice the opposite is often true: failures tend to occur not during full-load operation, but when the facility is used intermittently, left idle for long periods, and not properly maintained. The causes generally fall into three reasons:

I. Environment-related Risk

After a cold room is shut down, large temperature swings make condensation likely around the enclosure, door seals, and wall penetrations for piping and cables. When moisture migrates into the insulation, thermal performance declines; over time this can lead to sweating/condensation, mold growth, corrosion, and even floor frost heave or slab bulging.

II. Equipment-related Risk

When components such as compressors, evaporator fan motors, bearings, and contactors remain unused for a long time, issues can quietly accumulate—oil migration or drain-back, seal drying and cracking, oxidation of electrical contacts, and rodent damage to wiring, among others.

III. Eanagement-related Risk

Idle periods often come with reduced inspections and poor recordkeeping, so problems are discovered only when the cold room is needed again. By then, the time available for troubleshooting is short, and the result is often expensive unplanned downtime.

Therefore, the core approach for managing a rarely used cold room is not simply “turn it off and forget it,” but to treat it as an asset that requires: shutdown management + preservation protection + recommissioning verification.

What Kind of “Idle” Cold Room Do You Have?

Before taking action, clarify 3 things—these determine the strategy you should use.

-

Usage frequency: The cold room will use occasionally for turnover (a few days each month), seasonally (once every 6 months), or is it completely idle due to a production stoppage?

-

Temperature type: A high-temperature/chiller room (about 0–10°C), a low-temperature freezer (about -18°C), or a blast freezer (lower than -18°C and higher load).

-

Whether it has stored “high-risk goods”: such as seafood, meat, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, or biological products (which may involve odor residues, microbiological concerns, and compliance requirements).

You can roughly divide “idle” status into 3 tiers: short-term shutdown (a few weeks), mid-term shutdown (a few months), and long-term shutdown (more than half year).

The biggest differences among these tiers are: whether you need to fully cut power, whether requiere dehumidification and mold prevention, and whether the refrigeration system needs “preservation maintenance.”

Short-Term Shutdown (1–4 Weeks): Handling Procedure

Short-term shutdowns often happen during the off-season, brief production stoppages, or while waiting for goods. The goals are to keep the system ready for quick recovery, prevent condensation and odors, and reduce energy use.

1) Emptying and cleaning

Avoid leaving leftover cartons, pallets, and miscellaneous items in the room for long periods—especially paper packaging, which absorbs moisture, molds easily, and causes odors.

Clean floors and drains with a neutral detergent, focusing on corners, door areas, and under evaporators where dripping is common. After cleaning, keep the floor as dry as possible.

2) Choose “warm-hold operation” or “shutdown storage”

If you expect to use it again within two weeks, and the local environment is humid or door sealing is not ideal, we recommend to maintain a higher “holding” temperature—for example, keep a chiller room at about 8–12°C (depends), and let the system run for a period each day. This helps with dehumidification and keeps the compressor, fans, and electrical system in healthier condition.

If you don’t expect to use it and the room is completely dry, you can shut it down—but don’t cut main power immediately. Let fans run for a while, or ventilate by opening the door on dry-weather days to remove moisture.

3) Door sealing and pest control

A common short-term shutdown issue is: doors not fully closed or deformed gaskets allowing continuous moisture ingress. Check gasket elasticity and contact; adjust if needed.

Use physical rodent traps around the exterior floor and walls, and seal cable penetrations with firestop putty or other suitable sealing materials.

4) Simple inspections

At least once per week: check for abnormal frosting or dripping on evaporators, confirm control panel indicator lights are normal, listen for abnormal compressor noise, check for odors, and check the floor for standing water.

Mid-Term Shutdown (1–6 Months): Handling Procedure

The key for mid-term shutdown is moisture control and equipment preservation. This period is the most likely to develop mold, corrosion, electrical oxidation, and moisture intrusion into insulation.

1) Deep cleaning and disinfection (as needed)

For food use, consider moderate disinfection after cleaning to reduce residual mold spores. Avoid chemicals that are strongly corrosive to stainless steel or aluminum fins.

Clean evaporator fins gently to prevent deformation that would reduce heat transfer.

2) Thorough drying: more important than cleaning

Many cold-room odors come from incomplete drying. Options include ventilating with the unit off (choose dry weather date), using an industrial dehumidifier, or running fans for air circulation while dehumidifying.

The goal is that walls, floors, and corners feel dry to the touch.

3) Long-term dehumidification and mold prevention

For mid-term shutdown, consider placing desiccants or running dedicated dehumidification equipment, and placing anti-mold products near doors and corners (pay attention to compliance and food-contact risks).

If the room is well-sealed and the environment is humid, dehumidification becomes even more important; otherwise, the sealed space can become a “breeding chamber.”

4) Protect electrical and control systems

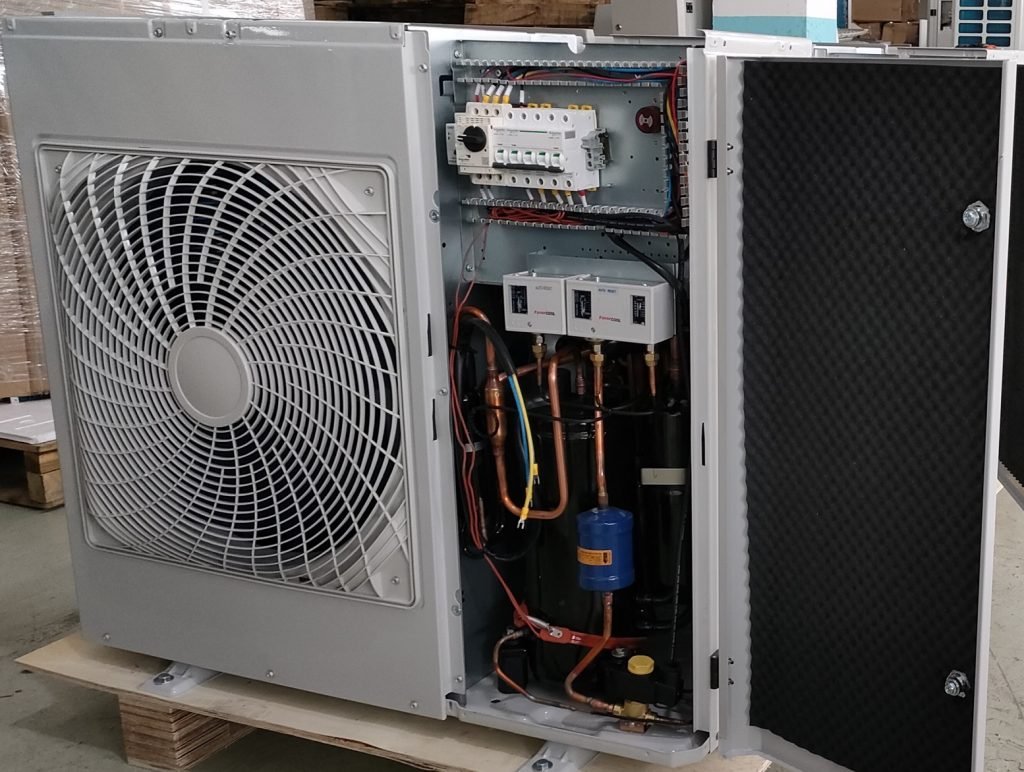

Moisture accelerates oxidation at terminals and in electrical panels. Keep control cabinets dry; if necessary, add small anti-moisture devices or desiccant packs.

For systems with electric defrost heaters or door-frame heaters, verify control logic during shutdown to avoid unintended heating, excess energy use, or localized overheating.

5) Operational preservation of the refrigeration system

Even when you don’t need cooling, we recommend to run the compressor briefly every 2–4 weeks (only if system conditions allow, oil level is normal, and qualified personnel confirm it is safe). This circulates lubricant and reduces seal drying.

For equipment that sits unused for long periods, lubrication and seal aging significantly increase recommissioning failure risk.

Long-Term Shutdown (More Than 6 Months): Handling Procedure

The purpose of Long-term shutdown is no longer immediate readiness, but slowing asset deterioration and minimizing safety risks.

1) Perform a “pre-shutdown health check” and keep records

Before full shutdown, record key data: refrigerant pressure (at standstill equilibrium), compressor oil level and oil condition, operating current (if measurable), evaporator/condenser cleanliness, control parameters, and alarm history. Take photos for documentation.

When restarting months later, this helps you determine whether issues are newly developed or pre-existing.

2) Preservation strategy: cut power, but don’t leave systems unprotected

Long-term shutdown typically involves cutting main power to reduce risk. Before power-off, ensure the room is dry, and protect control panels, junction boxes, and terminal strips from moisture.

Some sites place desiccant inside electrical cabinets and keep cabinet doors sealed.

3) Control risks to insulation and floor structure

Long-term shutdown requires special attention to floor slabs and insulation moisture.

If the cold room has anti-frost-heave measures (such as underfloor heating or ventilation), confirm whether any basic function must remain active to avoid structural damage. Because construction details vary widely, obtain clear shutdown guidance from the installer or maintenance provider.

4) Pest control and surrounding housekeeping

Idle cold rooms can become rodent “bases.” Address root causes: seal openings, remove clutter around the building, clean drainage channels, and regularly check for gnaw marks.

Damaged control wires and sensor cables are often discovered only at recommissioning, leading to higher repair costs and delayed restart schedules.

5) Optional: protect or remove key components for storage

If you expect shutdown to exceed one year and the environment is harsh (humidity, dust, salt spray), consider stronger protection: moisture-proof treatment for motors, anti-static storage for control boards, and shielding for external sensors. Whether to remove and store parts depends on site conditions and cost.

Pre-Start Checks and a “Gradual Recovery” Strategy

Don’t “turn everything on at once” in recommissioning!

The right approach is: confirm safety first, then system integrity, then reduce temperature gradually so equipment returns under mild conditions.

1) Structural and hygiene inspection

Check for mold spots, odors, and standing water; inspect door gaskets for aging; confirm lights and explosion-proof switches function; verify drainage is unobstructed.

For food use, cleaning and disinfection are often needed before restart.

2) Electrical safety inspection

Check whether electrical panels are damp, terminals are loose, grounding is reliable, and wiring has rodent damage.

If power has been off for a long time, should ideally supervise the first energization by an electrician or maintenance technician to prevent short circuits or component failures.

3) Basic refrigeration system inspection

Check compressor oil level and oil condition; look for oil stains on refrigerant piping (possible leak indicator); confirm fan blades rotate freely without binding; check whether the condenser is dirty or blocked.

If a refrigerant leak is suspected, don’t force start—perform leak detection and corrective actions first.

4) Staged operation

Run fans first to confirm airflow and no abnormal noise; then start the compressor briefly and observe current, pressures, and suction temperature; finally, gradually lower the setpoint from ambient down to the target temperature.

For freezer rooms, especially recommended staged pull-down to reduce frosting shock and mechanical stress.

For example: for a freezer with a target of -18°C, after a long idle period you can set it to -5°C for several hours, then to -12°C after stability is confirmed, and finally to -18°C.

The exact pace should be adjusted based on room size, unit capacity, and ambient humidity.

Maintenance Regime for Rarely Use: Stop Failures Early

If the cold room is not fully shut down but is used only occasionally, it is highly recommended to establish a lightweight maintenance routine—low cost, high return.

-

Fixed inspection frequency: every two weeks.

-

Three priorities: moisture (condensation/odor), electrical (terminals/alarms), and doors (gasket seal/closing rebound).

-

Operating habits: avoid repeatedly pulling down to very low temperatures and then shutting off quickly; reduce thermal shock and frosting.

-

Cleaning cycle: regularly remove dust from condenser heat-transfer surfaces; defrost and clean evaporators and drain pans.

-

Records: use a simple log (date—odor—standing water—alarms—temperature trend anomalies) to track patterns over time.

Common Misconceptions and Risk Points

-

Misconception 1: Shut down and keep the door tightly closed; moisture can’t escape, and odors worsen.

-

Misconception 2: Long shutdown with zero inspections; rodents damage wiring, discovered only at restart.

-

Misconception 3: On restart, immediately pull down to the final low temperature; rapid frosting and abnormal suction conditions overload the compressor.

-

Misconception 4: Watch only the compressor, ignore the condenser; dirty condensers cause high head pressure alarms and energy spikes.

-

Misconception 5: Use highly corrosive cleaners/disinfectants; fins and metal parts are damaged, trading short-term “clean” for long-term performance loss.

How to Decide: Keep, Retrofit, Sublease, or Scrap

When a cold room is rarely used, you also need a business decision: is it still worth keeping? A quick assessment can use four dimensions:

-

Asset condition: insulation moisture, floor integrity, equipment age, rising repair frequency.

-

Energy and maintenance cost: how much does minimum operation cost? Are annual maintenance and emergency repair costs controllable?

-

Business flexibility: is cold-chain capacity clearly needed to increase in the next 6–12 months? How volatile is demand?

-

Alternatives: the cost and risk of outsourced cold storage, shared cold-chain warehouses, or temporary cold room? etc.

If demand is only occasional, you may consider retrofitting it into a “medium-temperature turnover room” or rentable storage space to reduce the maintenance burden of deep-freezing.

If equipment is old and insulation is severely moisture-damaged, continued investment may be less economical than replacement or outsourcing cold room facility.

Conclusion

Effective management of an infrequently used cold room is less about “switching it off” and more about disciplined shutdown, preservation, and controlled recommissioning.

Moisture control, cleanliness, pest prevention, and periodic inspections protect insulation, electrical components, and rotating equipment from hidden degradation.

When restarting, verify safety and system integrity first, then run staged trials and pull temperature down gradually to avoid shock loads and icing.

With clear SOPs, checklists, and records, the cold room remains reliable, safe, and cost-effective even under low utilization.

Any comments?

Welcome leave a message or repost.